Yirrkala Dhunba

Yirrkala Dhunba is an Indigenous Australian artist whose practice spans painting, installation, and bioart. She explores the intersections of cultural knowledge, survival, and speculative science, bringing Indigenous voices into urgent conversations about climate change and biotechnology.

ARTIST STATEMENT

“My work speculates on how Indigenous futures might be re-sequenced under climate collapse. DIY CRISPR sets, data, and cultural symbols are placed side by side to ask: can gene editing ensure survival, or does it risk erasure? I want the lab to be both possibility and warning.”

Indigenous Genomic Adaptation

Indigenous Genomic Adaptation

Indigenous Genomic Adaptation

Indigenous Genomic Adaptation Indigenous Genomic Adaptation Indigenous Genomic Adaptation

Indigenous Genomic Adaptation (2023-)

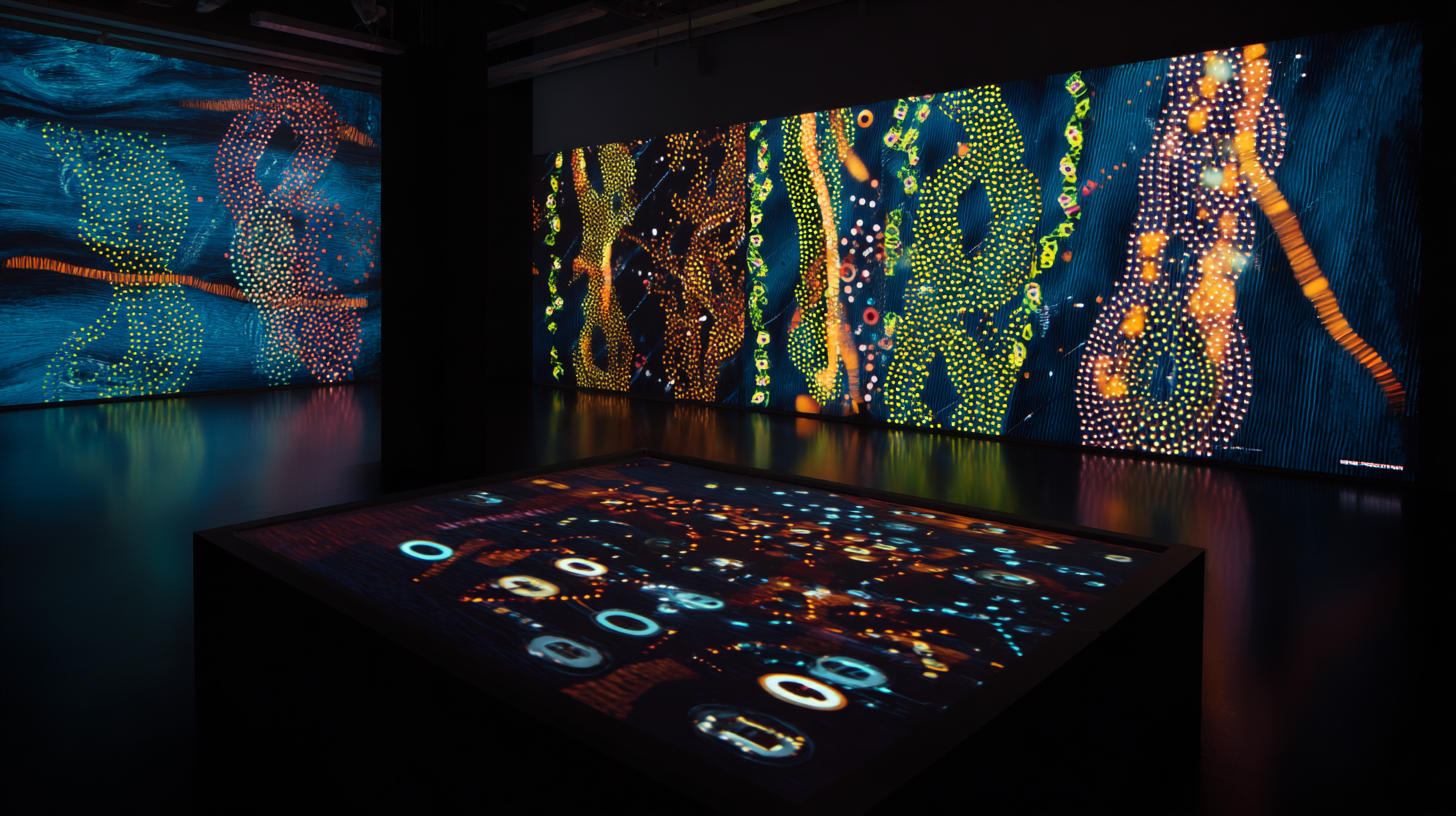

Indigenous Genomic Adaptation is a speculative bioart installation that stages a laboratory of survival. Petri-dish paintings with DNA mutations sit alongside DIY CRISPR sets, visualizing Indigenous futures re-sequenced under the pressure of climate change. Dhunba combines traditional aesthetics with speculative science, asking whether adaptation through AI and gene-editing can be a strategy for survival — and who has the authority to decide.

At its core, the work raises difficult ethical questions: can technology safeguard culture, or does it inevitably risk its erasure? Dhunba does not offer answers but insists that the debate itself must include Indigenous voices — not just as subjects of study, but as agents of design.

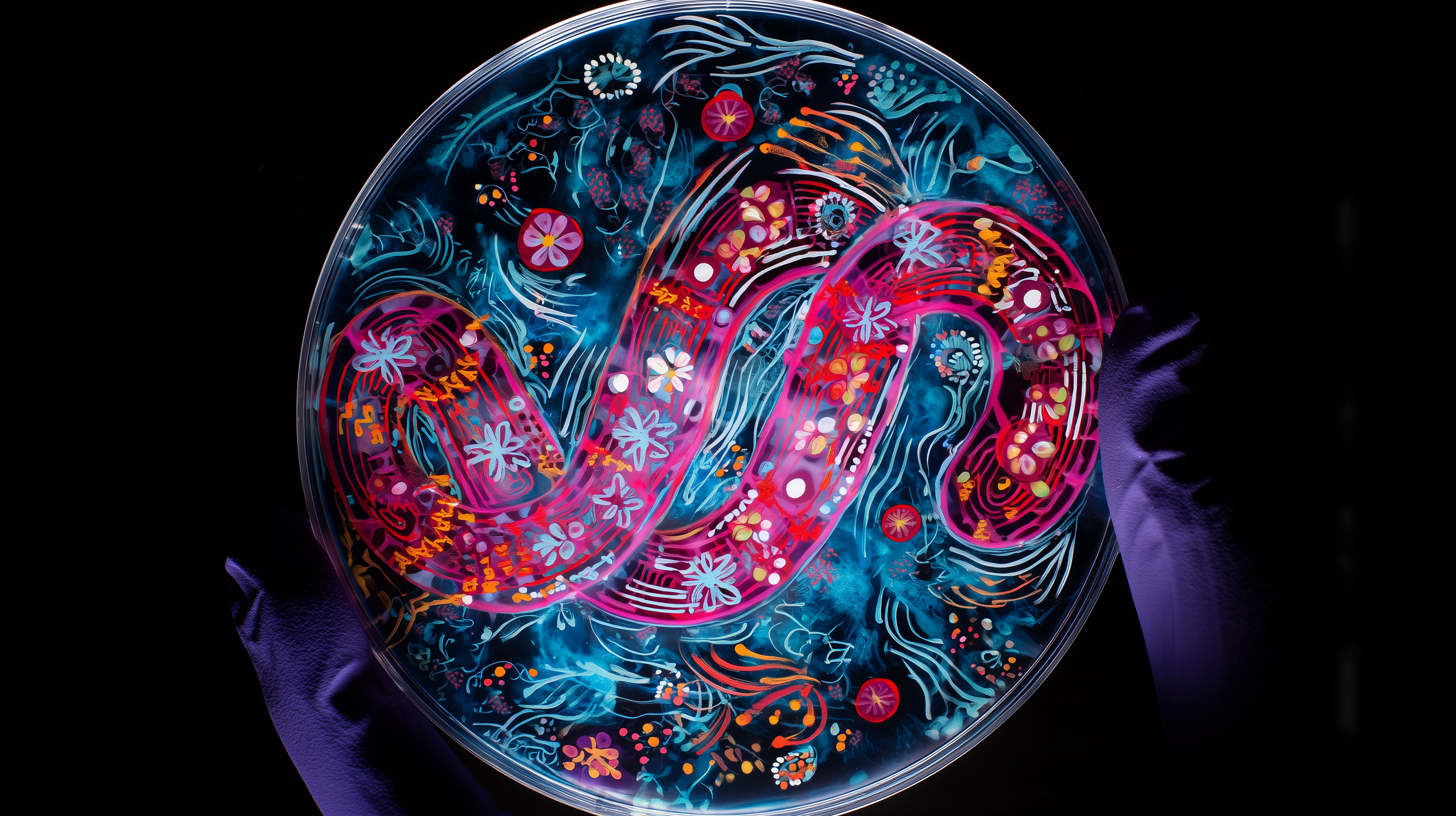

Detail from “Indigenous Genomic Adaptation” — hand-painted Petri dishes visualizing speculative DNA mutations, where cultural symbols meet molecular diagrams.

The artist in her speculative laboratory, working with DIY CRISPR kits and pigments drawn from Indigenous materials — blurring science, ritual, and resistance.

Speculative representation of genetically engineered Indigenous DNA — an imagined archive of survival, where technology becomes both threat and promise.

Speculative representation of genetically engineered Indigenous DNA — an imagined archive of survival, where technology becomes both threat and promise.

Installation view: data-driven interactive paintings reinterpreting genetic sequences through Indigenous aesthetics — translating code into ceremony.

5 questions

with yirkala dhunba

1. Your installation brings together cultural symbols and biotech lab equipment. How do you navigate the tension between these two very different worlds?

I don’t see them as opposites. Both culture and science are systems of knowledge, and both shape how we imagine survival. The tension comes from the fact that one has historically tried to dominate the other. My work forces them to sit in the same room, not in harmony but in confrontation.

2. When you were first featured in EE Journal in 2023, you described your practice as “art at the frontier of survival.” How has your thinking evolved since then?

Climate realities are accelerating faster than I imagined in 2023. That makes the work feel less speculative and more immediate. The frontier I spoke of has moved closer — now it feels like we are already inside the laboratory, already being asked to choose what parts of ourselves are preserved and what parts are lost.

3. How have Indigenous communities responded to the project?

With complexity. Some see it as empowering, others as deeply troubling. There is fear that by entering into the language of gene editing, we risk reinforcing the very frameworks that erase us. But there is also recognition that imagining survival on our own terms is a form of resistance. The mixed responses tell me the work is doing what it should: opening a debate that cannot be simplified.

4. Do you see AI as collaborator, threat, or something else in this context?

AI is a mirror of the systems that build it. In biotech it can accelerate discovery, but it also carries the same extractive logics that threaten Indigenous knowledge. For me, AI is not a collaborator but a provocation — a reminder that survival must be defined by those who live it, not by those who model it from afar.

5. If you had to imagine Indigenous Genomic Adaptation ten years from now, what would it look like?

It would not be static. Perhaps the lab would no longer be speculative, but a lived space of adaptation. Perhaps it would be dismantled, replaced by strategies of refusal and invisibility. The point is not to predict a single outcome, but to insist that Indigenous futures must be self-authored, whether through science, culture, or both.